|

|||||||||||||||

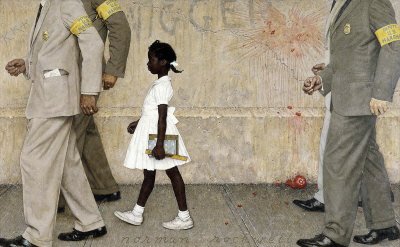

The Problem We All Live With by Norman Rockwell

January 14, 1964 Issue of LookThe Problem We All Live With, by Norman Rockwell, appeared on pages 22 and 23 of the Look magazine published January 14, 1964. Alternate titles for this painting are Walking To School and Schoolgirl With U.S. Marshalls. This painting is one of Rockwell's most recognizable works. This was the first Rockwell illustration published in Look magazine. The Problem We All Live With was actually painted in 1963 and published in 1964. There were three Look issues in 1964 that featured Rockwell paintings. This painting also appears in virtually every Rockwell commentary books ever written, as well such a classic picture should. It appears:

One study also appears on page 200 of the Norman Rockwell Catalogue. Several photographs used in the painting of this illustration, as well as the painting itself, are reproduced in Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera by Ron Schick on pages 200 through 203. The original oil on canvas painting, 36 x 58 inches or 91.5 x 147.5 mm, is part of the collection of the Norman Rockwell Museum of Stockbridge, Ma. The painting was purchased by the then Old Corner House Collection from Bernard Danenberg Galleries. Recently, on December 2, 2010, a study for this painting sold at auction at Sotheby's in New York City. The oil on photographic paper study, 12.75 x 19.5 inches or 32.5 x 49.5 cm, crushed its pre-auction estimate of $150,000 to $250,000 by posting a final hammer price of $854,000. I have seen pristine original copies of the complete magazine sell for over one hundred dollars on eBay. And to think it only cost twenty-five cents originally! And it was mint condition then, too.

The Events Behind The Problem We All Live WithGiclee Prints on Archival Paper: When Look magazine published The Problem We All Live With in 1964, the event depicted was already out of the news. This particular event happened in 1960. The problem, however, was far from vanquished, just as it is far from vanquished even today. The problem referred to is, of course, racism and all the trouble it causes. Racially segregated schools, bathrooms and restaurants were only visible manifestations of the root. Class prejudice,in my opinion, is just as evil as race prejudice, but that is a discussion for another time. The event so masterfully illustrated by Rockwell was the racial integration of the New Orleans public school system. After the 1954 United States Supreme Court decision, Brown vs Board of Education, racial segregation in public schools was ruled to be unconstitutional. So, on November 14, 1960, little six year old Ruby Bridges attended the then all white William Franz Elementary School at 3811 N Galvez St in New Orleans, Louisanna. She was not welcomed with open arms. She was escorted to school that first day and each following day by United States Marshalls. She was the only child in her classroom that first year. Many white children did not attend school that first year simply because Ruby was attending that school. And yet she persevered. The school was eventually integrated largely because of her courage and persistence. The Models for The Problem We All Live WithThe hand and body models for the U.S. Marshalls were Frederick J. Oczkowski, William Baldwin and William J. Obanhein. Photographs in Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera by Ron Schick reaveal that many different shots were taken for the Marshalls hands and bodies. There were actually three models who posed for the role of Ruby Bridges. They were all from the Stockbridge, Massachusetts area. One of the girls was Lynda Gunn. Again, photos in Behind The Camera, show the three young girls who posed. Ron Schick, the author of that book, states that the final figure in the finished painting is a composite of all three. On the Surface of The Problem We All Live WithThe Problem We All Live With is one of Norman Rockwell's most famous and loved paintings. Rockwell captured the essence of this little black girl's historic walk into school. She is accompanied and guarded by four United States Marshalls. These men are all white. All are wearing business suits. All are wearing yellow arm bands proclaiming their office. They also wear badges on the front of their suits. The marshalls are faceless. The images of the marshalls remind me of stone pillars, solid, strong and, if necessary, unmoveable. They needed to be strong and solid, because there was an ugly mob there to greet Ruby that first and every day of the first school year. They had their jobs to do. And, yet, their job was not necessarily just to protect young Ruby Bridges as much as it was to fulfill the instutition of the law. Rockwell shows us the court's order for integration in the jacket pocket of the lead Marshall closest to our viewpoint. Focus on Ruby BridgesThe focus of the painting, though, is little Ruby Bridges. This is as it should be. She is dressed in a dress that is pure white, a contrast to her dark skin. This is probably one of her best dresses, maybe even her best Sunday dress. She is carrying her two school books, her ruler and her pencils. She is staying right behing the two lead marshalls. She actually looks very brave, and indeed she was very brave, whether she realized it at the time or not. The only indication we can see of the mob at the school is the background of the painting. The background shows the mob's reaction to racial integration of the schools. A racial slur (that hateful "N" word) is scrawled on the wall in the center of the painting. The initials KKK also appear in the upper left corner of the background. A tomato has been thrown by a member of the mob. It looks as if it just barely missed little Ruby. That tomato was thrown so hard that its juice splattered in a radiant pattern and parts of its pulp are scattered on the wall. The spent tomato rests against the wall. The angle of the tomato's trajectory implies to us that little Ruby is walking right past the angry mob. And yet Ruby and her guardians press onward toward their goal. The Symbolism of The Problem We All Live WithRockwell did not usually make his paintings hard to understand. He painted for his readership, and that readership was, by and far, ordinary folks. By the same token, he always spent a great deal of time on details and getting his composition just like he wanted it to appear. The faceless United States Marshalls represent the power of the US government to enforce its rules. Their facelesssness shows the blindness of justice in a society ruled by law. The law is being enforced without consideration to the majority of the people involved in this episode. That majority, not shown except through the inferences of the tomato and racial epithets, does not want that school integrated. Their opinion and wishes do not change the rule of law or its enforcement. Another important symbol is the white dress Ruby is wearing. Ruby Bridges's motives were pure. She was not aware that she would become such an historic figure. She was only a little girl going to school. Contrast Ruby's innocent motives with the angry mob. That mob is symbolized by the tomato, bright red and shattered with its life force crushed, released and running in too many different directions to be sustained. Showing some irony, Rockwell painted the detritus from the thrown tomato only soiling the racial slur on the wall of the school. In contrast to Ruby and her school supplies, the tomato and the Marshall's badges and armbands, the whole rest of the painting is rendered in muted tones, pastels and grey tones. Reactions to The Problem We All Live WithRockwell received many letters in response to The Problem We All Live With. Many were positive, many were negative. Letters to the editor were a mix of praise and criticism. One Florida reader wrote, "Rockwell's picture is worth a thousand words . I am saving this issue for my children with the hope that by the time they become old enough to comprehend its meaning, the subject matter will have become history." Other readers objected to Rockwell's image. A man from Texas wrote "Just where does Norman Rockwell live? Just where does your editor live? Probably both of these men live in all-white, highly expensive highly exclusive neighborhoods. Oh what hypocrites all of you are!" The most shocking letter came from a man in New Orleans who called Rockwell's work, "just some more vicious lying propaganda being used for the crime of racial integration by such black journals as Look, Life, etc." But irate opinions did not stop Rockwell from pursuing his course. In 1965, he illustrated the murder of civil rights workers in Philadelphia, Mississippi, and in 1967, he chose children, once again, to illustrate desegregation, this time in our suburbs. While he was much loved and respected during his stint at the Saturday Evening Post, Rockwell was not allowed to pursue artistic means to effect social change. And especially not the kind of social change shown in this painting. The magazine cover and advertising illustrations he painted only allowed for minorities to be shown in roles as service personell. He did manage to make a waiter appear as one of the main characters in Boy in Dining Car, but he was still portrayed as a waiter. So Rockwell's fans were not accustomed to seeing him paint minorities very much at all. That all changed with The Problem We All Live With. Most of the subject matter Rockwell's paintings dealt with popular timely subjects. After all, he had painted America as he wanted it to be for almost forty years. His fans were also not accustomed to seeing him portray any type of controversy. Some of the reactions to The Problem We All Live With totally missed what Rockwell was trying to convey. Some of the comments indicated that the writer thought that Rockwell believed that black people were the problem we all live with, the "we" being white people. Some thought that integration was the problem. Of course, Rockwell, being a man who loved and lived tolerance and equality, was saying that the racism depicted in the painting is the problem. He was also pointing out that the end of racial segregation would not end racism. No, the end of racism will take much more to accomplish than merely requiring different races to live, work and attend school together. Racism will endure until all forms of hatred, no matter the basis, are conquered by love. Tolerance by itself just will not accomplish the goal of ending racism. Some of the reactions on the internet that I found while researching this article astounded me. Some I agree with, some I do not. One author said the proof that Rockwell and this painting was not racist in attitude or execution was how the United States Marshalls were depicted. Cropping their heads and faces focused the attention on the little black girl. The writer brought up the point that, had the Marshalls taken the focus away from Ruby, that could have been a racist gesture. The only white skin in The Problem We All Live With is found on the Marshalls' clenched fists. The only white skin is shown as ready to protect and defend Ruby Bridges. Once again, Rockwell has composed a masterpiece. Once again, Rockwell has made us think about a complex subject.

Norman Rockwell's The Problem We All Live With (1964)

Remember to check back often.

|

Norman Rockwell Quotes:I'll never have enough time to paint all the pictures I'd like to. No man with a conscience can just bat out illustrations. He's got to put all his talent and feeling into them! Some people have been kind enough to call me a fine artist. I've always called myself an illustrator. I'm not sure what the difference is. All I know is that whatever type of work I do, I try to give it my very best. Art has been my life. Right from the beginning, I always strived to capture everything I saw as completely as possible. The secret to so many artists living so long is that every painting is a new adventure. So, you see, they're always looking ahead to something new and exciting. The secret is not to look back. I can take a lot of pats on the back. I love it when I get admiring letters from people. And, of course, I'd love it if the critics would notice me, too. You must first spend some time getting your model to relax. Then you'll get a natural expression. More at BrainyQuote. Rockwell Favorites

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Images are copyrighted by their respective copyright holders. Graphic Files Protected by Digimarc. Contact us for details about using our articles on your website. The only requirements are an acknowledgement and a link.

|

|||||||||||||||